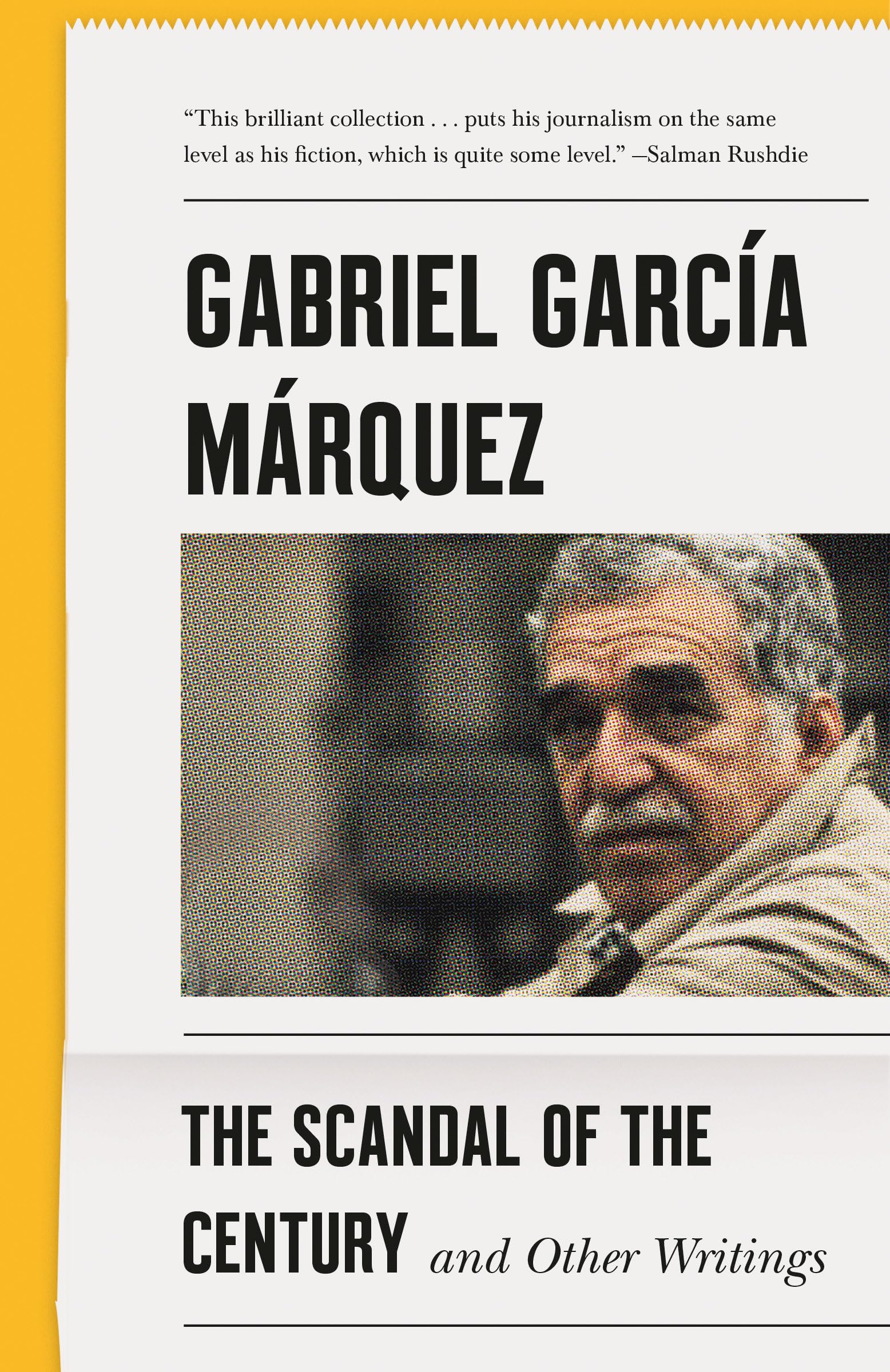

Collected here for the first time: a selection of the great writer's journalism, which he considered more important to his legacy than his acclaimed novels. Late in his life, Gabriel García Márquez declared: “I don’t want to be remembered for One Hundred Years of Solitude , nor for the Nobel Prize, but rather for the newspaper. I was born a journalist. . . . It’s in my blood.” Now available for the first time in English, this selection offers a glimpse into the great novelist’s career as a reporter. Ranging from the early pieces he wrote while starting out in Colombia to his longer reportage from Paris and Rome and, later on, from Venezuela and Mexico, these fifty journalistic writings amply display the narrative gifts that made his reputation. The Scandal of the Century is a tribute to García Márquez’s dedication to the profession he believed to be “the best in the world.” “This brilliant collection . . . puts his journalism on the same level as his fiction, which is quite some level.” —Salman Rushdie “ The Scandal of the Century demonstrate[s] that his forthright, lightly ironical voice just seemed to be there, right from the start. . . . He had a way of connecting the souls in all his writing, fiction and nonfiction, to the melancholy static of the universe.” — The New York Times “This collection is a master class on how to write for a newspaper: lush, vivid columns full of information, irony, whimsy, humor, skepticism and rumination, just what one would expect.” —Seymour M. Hersh “Márquez’s fiction would not exist without his journalism, just as without his fiction his journalism would not exist: they nourished each other. Some of [his] journalistic pieces are every bit as good as his fiction at its best.” —Javier Cercas, author of Lord of All the Dead Gabriel García Márquez was born in Colombia in 1927. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1982. He is the author of many works of fiction and nonfiction, including One Hundred Years of Solitude and Love in the Time of Cholera . He died in 2014. Editor’s Note To the memory of Carmen Balcells and Claudio López de Lamadrid Gabriel García Márquez called journalism “the best job in the world,” and he identified more as a journalist than a writer: “I am basically a journalist. All my life I have been a journalist. My books are the books of a journalist, even if it’s not so noticeable,” he once said. These fifty journalistic pieces by García Márquez, published between 1950 and 1984, were selected from the hundreds compiled in Jacques Gilard’s monumental five-volume collection, Obra periodística , in order to provide readers of his fiction a sample of his writings for the newspapers and magazines for whom he worked a great part of his life. He always considered his training as a journalist the foundation of his work in fiction. In many of the writings collected here, readers of his novels and short stories will find a recognizable narrative voice in the making. Those who want to delve into the subject can find an exciting and erudite explanation of García Márquez’s journalism career in the prologues of Gilard’s compilation. As Gilard wrote, “García Márquez’s journalism was mainly an education for his style, and an apprenticeship toward an original rhetoric.” The first works of journalism published as books were the reportage Relato de un naúfrago ( The Story of a Ship-wrecked Sailor, 1970) and an anthology of articles written in Venezuela, Cuando era feliz e indocumentado ( When I Was Happy and Undocumented, 1973). Crónicas y reportajes ( Chronicles and Reportages ), a selection made by the author, was published in 1976 by the Instituto Colombiano de Cultura. A compendium selected by García Márquez’s journalist col- leagues, Gabo periodista, published in 2012 by the Fundación para el Nuevo Periodismo Iberoamericano and Mexico’s Conaculta, also provides a detailed chronology of his career. Although some of his first fictional stories were written before he worked as a reporter, it was journalism that allowed the young García Márquez to leave his law studies and start writing for El Universal in Cartagena and El Heraldo in Barranquilla. He later traveled to Europe as a correspondent for El Espectador of Bogotá. Upon his return, and thanks to his friend and fellow journalist Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza, he continued to write in Venezuela for the magazines Élite and Momento, until moving to New York City in 1961 as a correspondent for the Cuban news agency Prensa Latina. Later that year he settled in Mexico City with his wife, Mercedes Barcha, and his son Rodrigo, where he published No One Writes to the Colonel, began working in screen- writing, and later devoted all his time to writing One Hundred Years of Solitude . Although his work as a writer would occupy most of his time, he always returned to his passion for journalism. During his lifetime he founded six publications, including Alterna