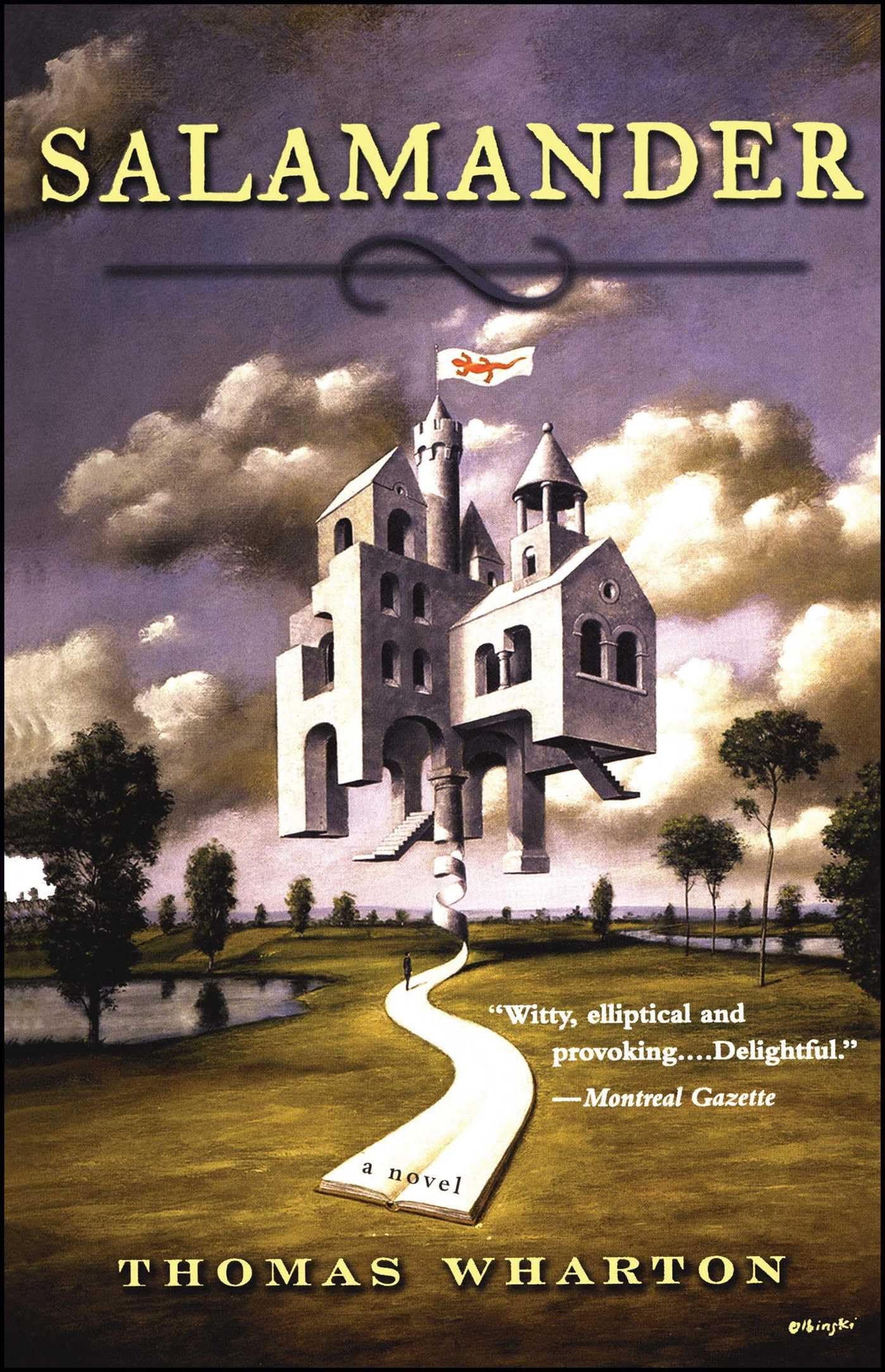

Nicholas Flood, an unassuming eighteenth-century London printer, specializes in novelty books -- books that nestle into one another, books comprised of one spare sentence, books that emit the sounds of crashing waves. When his work captures the attention of an eccentric Slovakian count, Flood is summoned to a faraway castle -- a moving labyrinth that embodies the count's obsession with puzzles -- where he is commissioned to create the infinite book, the ultimate never-ending story. Probing the nature of books, the human thirst for knowledge, and the pursuit of immortality, Salamander careens through myth and metaphor as Flood travels the globe in search of materials for the elusive book without end. Montreal Gazette Witty, elliptical and provoking...Delightful. Edmonton Journal This novel cannot help but connect deeply with its readers...[It is] a sprawling, lush fable that is equal parts adventure, romance, treatise, and history...[Wharton] strikes off across an exotic terrain already brilliantly traversed by such figures as Umberto Eco, Jorge Luis Borges, and Italo Calvino. Quill & Quire A vigorous, imaginative novel about the power of reading and invention. The Globe and Mail (Toronto) Salamander leaves an exotic flavour in the mouth, and will reward its readers with the sense that they have been taken on a strange journey. Thomas Wharton's first novel, Icefields, won the Writers Guild of Alberta Best First Book Award and the Banff Mountain Book Festival Grand Prize. It is available from Washington Square Press. Wharton lives in Edmonton, Canada, with his wife and children. Salamander By Thomas Wharton Washington Square Press Copyright © 2002 Thomas Wharton All right reserved. ISBN: 0743444159 1759 A burning scrap of paper drifts down out of the rain. A magic carpet on fire. It falls with a hiss to the wet stones of the street. The colonel dismounts from his horse and stands holding the reins, his eyes raised to the sky. The light rain that began as he entered the town has drawn off. The grey clouds are shredding away to reveal patches of deep blue twilight. Wind moans from within the black hole that was once the building's entrance, like the sound from a shell held to the ear. There is a flicker of candlelight deep within the shadows of the bombed-out ruins. There shouldn't be. Sheltering in such places has been forbidden by decree of the governor. The colonel ties his horse to a nearby rail and climbs a ridge of fallen brick to enter the building. The smoke, the drifting ash tell him that the bomb struck quite recently. Only a few hours ago, if his judgement of these things is correct. A wigwam of smouldering timbers fills the middle of the narrow main floor, and he has to walk along the wall to proceed any deeper into the shop, for a shop of some kind it seems to have been, stepping carefully over wet and treacherous wooden wreckage. He feels a drop of rain on his face and glances up to see luminous patches of cloud through a cross-hatching of scorched and amputated beams. A bookshop. Three of four huge glass-fronted bookcases that once lined the long walls have been smashed open, the books they contained scattered about the room. The one case that remains standing now leans backward as if half-sunk into the wall, its glass panels gone but a few of the books still intact on its shelves. Along the side walls ancient stonework appears in the places where plaster has fallen loose. Two men are browsing through the books that remain on the shelves. They glance at the colonel, take in his uniform, put down the books they were examining and hurry out with furtive backwards glances. Looting has become a hanging offense in the abandoned town. In the waning light the colonel gazes in wonder at the bizarre volumes issued by destruction. Books without covers. Covers without books. Books still smouldering, books reduced to mounds of cold, wet ash. Shredded, riddled, and bisected books. Books with spines bent and snapped, one transfixed by a jagged black arrow of shrapnel. In one dark corner lies the multi-volume set of an outdated atlas, fused into a single charred mass. The gold lettering on the spines has somehow survived the fire and glows eerily from the shadows. Why is the world so made, the colonel wonders, that whatever is damaged shines? As he steps forward the colonel's foot strikes another volume, one without a cover. It lies splayed open, its uppermost pages lifting and falling with the gusts of evening wind. A huge grey moth, sealed in its unknowable moth self. Further back, where the roof is still intact, he finds the source of the light he saw from the street. Candles everywhere, in brackets, in crevices and holes blasted through the masonry. At the back of the shop, in the midst of the light, a young woman crouches amid a great heap of splintered wood, picking up and setting down one piece after another, as if searching for something. Above her on wires strun