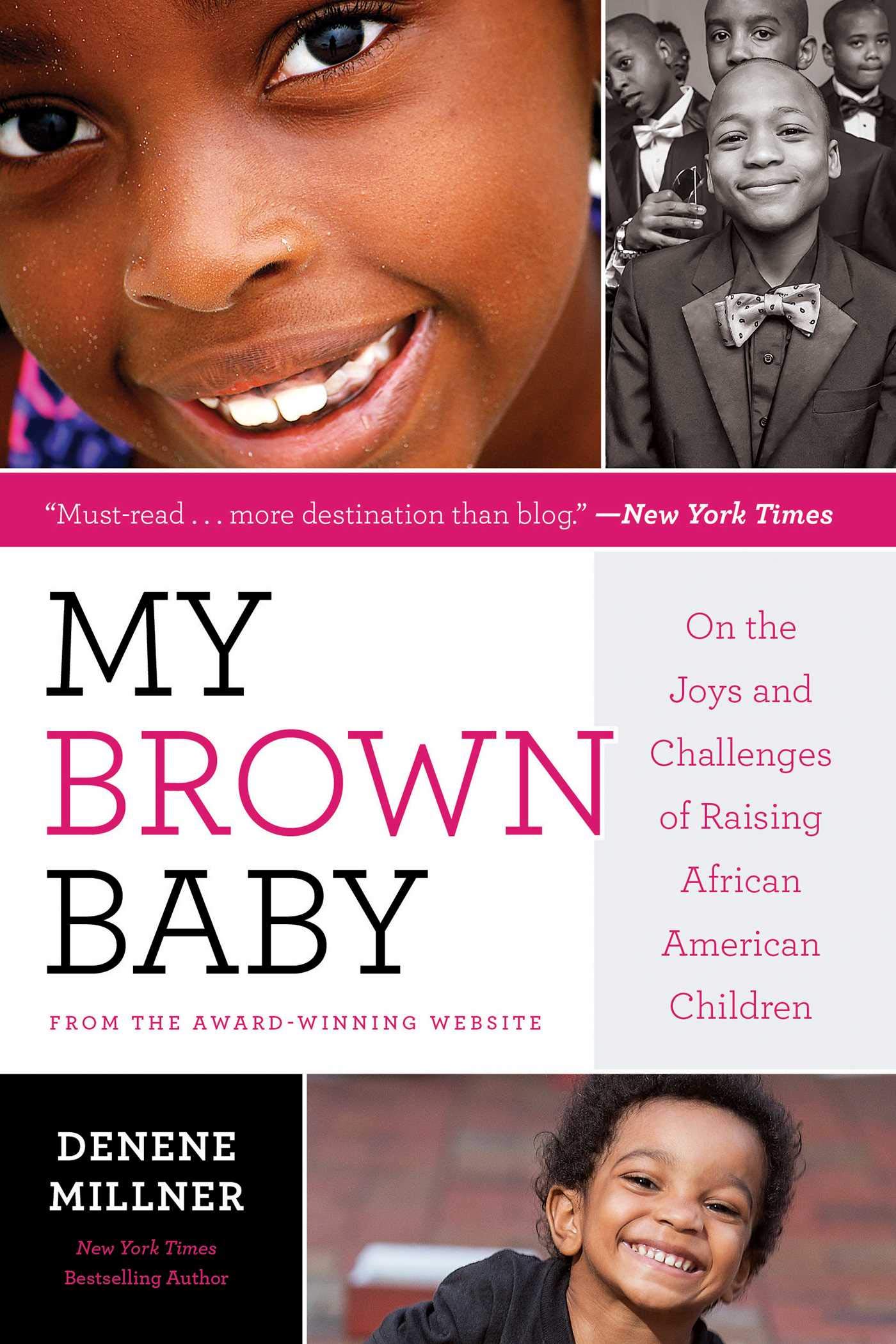

From noted parenting expert and New York Times bestselling author Denene Millner comes the definitive book about parenting African American children. For over a decade, national parenting expert and bestselling author Denene Millner has published thought-provoking, insightful, and wickedly funny commentary about motherhood on her critically acclaimed website, MyBrownBaby.com. The site, hailed a “must-read” by The New York Times , speaks to the experiences, joys, fears, and triumphs of African American motherhood. After publishing almost 2,000 posts aimed at lifting the voices of parents of color, Millner has now curated a collection of the website’s most important and insightful essays offering perspectives on issues from birthing while Black to negotiating discipline to preparing children for racism. Full of essays that readers of all backgrounds will find provocative, My Brown Baby acknowledges that there absolutely are issues that Black parents must deal with that white parents never have to confront if they’re not raising brown children. This book chronicles these differences with open arms, a lot of love, and the deep belief that though we may come from separate places and have different backgrounds, all parents want the same things for our families—and especially for our children. Denene Millner is a New York Times bestselling author, award-winning journalist, and director of the Denene Millner Books imprint. She has written more than thirty books for adults, teens, and children, among them her novel One Blood , a multi-generational epic about motherhood and adoption, and Early Sunday Morning, a children’s picture book. She is the host of Speakeasy with Denene , a podcast produced by Georgia Public Broadcasting. A MacDowell Fellow, Denene lives in Atlanta with her two daughters and their adorable Goldendoodle, Teddy. Visit her at DeneneMillner.com. Chapter 1: My Escort into Motherhood CHAPTER 1 My Escort into Motherhood I WAS A YOUNG REPORTER WHEN I MET HER—full of energy, I had a flat stomach, still 120 pounds soaking wet, still eating popcorn and rainbow sherbet for dinner. Despite having awesome health insurance, I’d gone years without seeing a doctor of any kind. When you’re in your 20s, lying on a table with your legs up in the air while a total stranger peers at and feels all over your goodies is never at the top of your list of things to do. But she insisted I come see her. A woman, she said, needs to keep track of her health—no matter how uncomfortable, no matter how busy, no matter how fearful, no matter what. And so I called her office and made an appointment and not even two weeks later, I was on Dr. Hilda Hutcherson’s table, having my lady parts examined. I’d submitted to nurse practitioners at local clinics when I was a college student; how else to get low-cost birth control without involving your parents? But Hilda was my first real gynecologist. Work brought her to me and me to her; as a young features writer for the New York Daily News , I was searching for a story to whip up for Mother’s Day, and her book, Having Your Baby: For the Special Needs of Black Mothers-To-Be, from Conception to Newborn Care , just happened to be floating around the newsroom; it just made sense for me to write a piece about the joys and challenges of black mothers. Mind you, I didn’t have any babies of my own—wasn’t even thinking about being a mother anytime soon. But even then, back in 1997, a full two years before I would have a baby of my own, giving a voice to and telling the stories of African American mothers was important to me. Necessary. Witness what Hilda told me when, for a Daily News Mother’s Day story I penned about her back in the mid-1990s, I asked her how she balanced a thriving Upper East Side practice, writing books, and a husband and four kids. Here’s how she answered: It’s a tradition of mothering that goes back hundreds of years,” Hutcherson offers simply. “I think that black women have always been valiant for their ability to do multiple things at the same time. They mother their children and take care of other people’s children, sometimes breast-feeding your baby and their babies, too… take care of the household, raise children, be a wife, work hard for little recognition and pay, and do it all well on limited means. I think that was very hard for my mother, her mother and other African American women but somehow they managed. I was always taught that I could, too. Sure, some could argue that the civil rights movement and Martin Luther King, Jr. made it so that, today, there’s really no difference between, say, an African American mother with a career and a white counterpart with all the same responsibilities. But that counterpart probably wouldn’t have thought about it for longer than two minutes. Most African American women will tell you there’s an added struggle with being a black mother—an extra pile of junk in the trunk. There are the stereotypes